| The hepatitis B

virus consists of a core containing DNA and a DNA polymerase enzyme needed for

virus replication. The core of the virus is surrounded by surface protein . The virus, also called a Dane particle,

and an excess of its surface protein (known as hepatitis B surface antigen)

circulate in the blood. Humans are the only source of infection.

|

| . Hepatitis B surface antigen

(HBsAg) is a protein which makes up part of the viral envelope. Hepatitis B core

antigen (HBcAg) is a protein which makes up the capsid or core part of the virus

(found in the liver but not in blood). Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) is part of

the HBcAg which can be found in the blood and indicates

infectivity. |

| Hepatitis B

infection affects 300 million people and is one of the most common causes of

chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma world-wide.

|

| Hepatitis B may

cause an acute viral hepatitis; however, the acute infection is often

asymptomatic, particularly when acquired at birth. Many individuals with chronic

hepatitis B are also asymptomatic. Chronic hepatitis, associated with elevated

serum transaminases, may occur and can lead to cirrhosis, usually after decades

of infection |

The risk of

progression to chronic liver disease depends on the source of infection Vertical transmission, from mother to child in the perinatal period,

is the most common cause of infection world-wide and carries the highest risk. |

SOURCE OF HEPATITIS B

INFECTION AND RISK OF CHRONIC INFECTION

|

| Route of transmission |

Risk of chronic infection |

| Horizontal

transmission |

10% |

| Injection drug use |

|

| Infected unscreened blood

products |

|

| Tattoos/acupuncture

needles |

|

| Sexual (homosexual and

heterosexual) |

|

| Vertical

transmission |

90% |

| HbsAg-positive

mother |

|

| There is an initial

immunotolerant phase with high levels of virus and normal liver biochemistry. An

immunological response to the virus then occurs, with elevation in serum

transaminases which causes liver damage: chronic hepatitis. If this response is

sustained over many years and viral clearance does not occur promptly, chronic

hepatitis may result in cirrhosis. In individuals where the immunological

response is successful, viral load falls, HBe antibody develops and there is no

further liver damage. Some individuals may subsequently develop HBV-DNA mutants,

which escape from immune regulation, and viral load again rises with further

chronic hepatitis. Mutations in the core protein result in the virus's inability

to secrete HBe antigen despite high levels of viral replication; such

individuals have HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis. (ALT = alanine

aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase) |

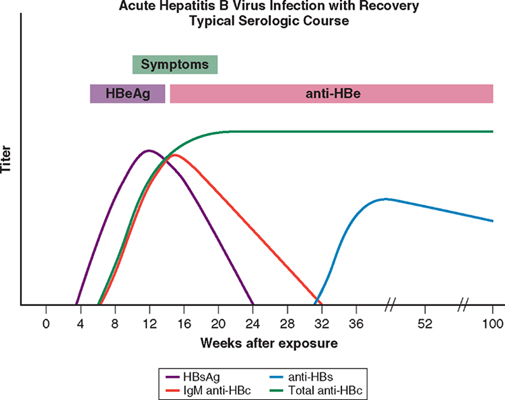

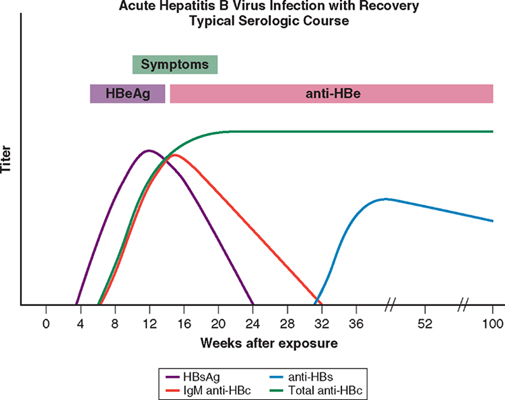

| (HBsAg = hepatitis

B surface antigen; anti-HBs = antibody to HBsAg; HBeAg = hepatitis B e antigen;

anti-HBe = antibody to HBeAg; anti-HBc = antibody to hepatitis B core

antigen) |

INTERPRETATION OF MAIN

INVESTIGATIONS USED IN THE SEROLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS OF HEPATITIS B VIRUS

INFECTION

|

| |

|

Anti-HBc |

|

| Interpretation |

HBsAg |

IgM |

IgG |

Anti-HBs |

| Incubation

period |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

| Acute

hepatitis |

| Early |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

| Established |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

| Established

(occasional) |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

| Convalescence |

| (3-6 months) |

- |

± |

+ |

± |

| (6-9 months) |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

| Post-infection |

| > 1 year |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

| Uncertain |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

| Chronic

infection |

| Usual |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

| Occasional |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

| Immunisation without

infection |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

|

+ positive; -

negative; ± present at low titre or absent. |

| HBV contains

several antigens to which infected persons can make immune responses these antigens and their antibodies are

important in identifying HBV infection |

| In acute infection

the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is a reliable marker of HBV infection,

and a negative test for HBsAg makes HBV infection very unlikely but not

impossible . HBsAg appears in the blood late in the

incubation period and before the prodromal phase of acute type B hepatitis; it

may be present for only a few days, disappearing even before jaundice has

developed, but usually lasts for 3-4 weeks and can persist for up to 5 months.

|

| Antibody to HBsAg

(anti-HBs) usually appears after about 3-6 months and persists for many years or

perhaps permanently. Anti-HBs implies either a previous infection, in which case

anti-HBc (see below) is usually also present, or previous vaccination when

anti-HBc is not present. |

| The hepatitis B

core antigen (HBcAg) is not found in the blood, but antibody to it (anti-HBc)

appears early in the illness and rapidly reaches a high titre which then

subsides gradually but persists. Anti-HBc is initially of IgM type with IgG

antibody appearing later. Anti-HBc (IgM) can sometimes reveal an acute HBV

infection when the HBsAg has disappeared and before anti-HBs has developed (and |

| The hepatitis B e

antigen (HBeAg) appears only transiently at the outset of the illness and is

followed by the production of antibody (anti-HBe). The HBeAg reflects active

replication of the virus in the liver. The persistence of HBsAg for longer than

6 months indicates chronic infection. |

| Chronic HBV

infection (see below) is marked by the presence of HBsAg and anti-HBc (IgG) in

the blood. Usually, HBeAg or anti-HBe is also present; HBeAg indicates continued

active replication of the virus in the liver while anti-HBe implies that

replication is occurring at a much lower level or that HBV-DNA has become

integrated into host hepatocyte DNA. |

| HBV-DNA encodes four proteins: a DNA

polymerase needed for viral replication (P), a surface protein (S), a core

protein (C) and an X protein. The pre-C and C regions encode a core protein and

an e antigen. Although mutations in the hepatitis B virus are frequent

occurrences, certain mutations have important clinical effects. Pre-C encodes a

signal sequence needed for the C protein to be secreted from the liver cell into

serum as e antigen. A mutation in the pre-core region leads to a failure of

secretion of e antigen into serum and so individuals have high levels of viral

production but no detectable e antigen in the serum. Mutations can also occur in

the surface protein and may lead to the failure of vaccination (surface

antibodies produced against native S protein) to prevent infection. Mutations

also occur in the DNA polymerase during antiviral treatment with

lamivudine. |

| HBV-DNA can be

measured by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the blood. Viral loads are

usually in excess of 105 copies/ml in the presence of active viral

replication, as indicated by the presence of e antigen. In contrast, in those

with low viral replication, HBsAg- and anti-HBe-positive, viral loads are less

than 105 copies/ml. The exception is in patients who have a mutation

in the pre-core protein, which means they cannot secrete e antigen into serum . Such individuals will be anti-HBe-positive

but have a high viral load and often evidence of chronic hepatitis. These

mutations are common in the Far East and those affected are classified as having

e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis. They respond differently to antiviral

drugs from those with classical e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis.

|

| Measurement of

viral load is important in monitoring antiviral therapy and identifying patients

with pre-core mutants. Specific HBV genotypes can also be identified using PCR.

Genotypes B and C appear to have more aggressive disease that responds less well

to antiviral therapy. |

| Treatment is

supportive with monitoring for acute liver failure, which occurs in less than 1%

of cases. |

| Treatments are

still limited, with no drug able to eradicate hepatitis B infection completely.

The indication for treatment is a high viral load in the presence of active

hepatitis, as demonstrated by elevated serum transaminases and/or histological

evidence of inflammation. |

| This is most

effective in selected patients with a low viral load and serum transaminases

greater than twice the upper limit of normal in whom it acts by augmenting a

native immune response. In HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis 33% lose e antigen

after 4-6 months of treatment compared to 12% of controls. Response rates are

lower in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis, even when patients are given longer

courses of treatment. Interferon is contraindicated in the presence of cirrhosis

as it may cause a flare in serum transaminases and precipitate liver failure.

Longer-acting pegylated interferons which can be given once weekly have been

evaluated in both HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis . Other antiviral therapies are required because many patients with

chronic hepatitis B have high levels of viraemia and/or low transaminase levels

and are not therefore candidates for interferon. |

PEGYLATED INTERFERONS IN

CHRONIC HEPATITIS B INFECTION

|

| 'In HBeAg-positive

chronic hepatitis treatment with pegylated interferon for 6 months eliminates

HBeAg in 35%, and normalises liver biochemistry in 25% of patients. In

HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis treatment with pegylated interferon for 12

months leads to normal liver biochemistry in 60%, and sustained suppression of

hepatitis B virus load below 400 copies/ml in 20% of

patients.' |

|